innovation-matters.info

A community for innovators

Optimizing ecosystem configuration

and governance with an ecology lens

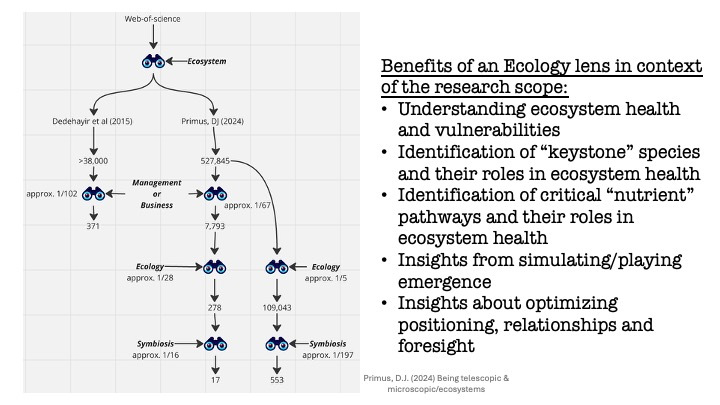

Is the ecosystem metaphor just a rebranding for established concepts like technology clusters and innovation networks, or does it represent actual, substantive differences between clusters, networks and modern "innovation ecosystems"? Can the important characteristics of modern forms of organizing innovation be captured by using an ecology lens? The left half of the figure below indicates that the presence of the ecosystem perspective in Management or Business studies is growing. However, while the number of publications that use the term "Ecosystem" has increased significantly in the last decade, the presence of an "ecology lens" is comparably low in Management or Business fields. To examine the actual significance of the "eco" in this context, highly regarded innovation scholars (Ritala and Almpanoupolou, 2017) have written articles "in defense of the 'eco' in innovation ecosystems". The figure below highlights some of the benefits of an ecology lens in innovation ecosystems research, such as identifying "keystone species" - entities with disproportionate influence on ecosystem health and stability. CSIRO (the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) exemplifies such a keystone organization in Australia's innovation landscape, performing a role comparable to how the Cassowary functions as a keystone species in natural Australian ecosystems.

A small collection of research has examined how an ecological perspective can enhance our understanding of innovation ecosystems. This line of inquiry can provide use cases for the ecology lens, supporting both innovation practitioners and policymakers. It helps them shape the configuration and governance of a dynamic, evolving array of actors (e.g. businesses, universities, investors, governments) who interact within the shared environment of an innovation ecosystem. Notable examples are (in the opinion of the creators of this community) the exquisite research articles by Shaw and Allen (2018) and Dedehaydir et al (2018) in the journal Technological Forecasting and Social Change. More recently, Primus (2024) presented his ongoing research project that employs an ecology lens at the ISPIM (International Society of Professional Innovation Managers) conference in Osaka, Japan. The abstract reads as follows:

Driven by a considerable shift in how innovation activities are organized and understood, the ecosystem perspective has garnered increasing attention in innovation management literature in recent years. Innovation ecosystems are characterized by loose contractual structures, distributed value creation and governance, as well as integrating and aligning different yet interrelated technological components towards a shared purpose (Ritala and Thomas, 2025; Baldwin et al, 2024). While the frequency of using the ecosystem metaphor has increased significantly in innovation research and practice, the principles of natural ecology have been underutilized in the analysis of and prescriptions for innovation ecosystems (Oh et al, 2016). This research project aims to generate novel insights that inform practice and theory on ecosystem configuration and governance going beyond physical, contractual and influence attributes of networked relationships, as well as location-based economic factors of the system. Building and maintaining a prosperous innovation ecosystem presents significant challenges, comparable to natural ecosystems. Recent practitioner studies suggest that many ecosystems fail because of the wrong ecosystem configuration or poor government choices about membership (Pidun et al, 2020). In a hermeneutic circle, this project follows the evolution of the parts (microscopic) and the whole (telescopic) of several ecosystems surrounding digital innovations. Tracking ecosystem evolution from minimum viable ecosystem to climax community, ecosystems’ relationships are examined based on sub-types of symbiosis and ecosystems’ properties are measured via function, condition and resilience indicators. The first findings include novel insights into ecosystem vulnerabilities, relationship optimization, and pathways of value units. Unexpected insights highlight new ways of understanding competitive landscapes, regulatory challenges, and technological disruption risks. Additionally, the data suggests that contributing to ecosystem diversity and maintaining positive symbiotic relationships can elevate the legitimacy and stability of a nascent business in the ecosystem.

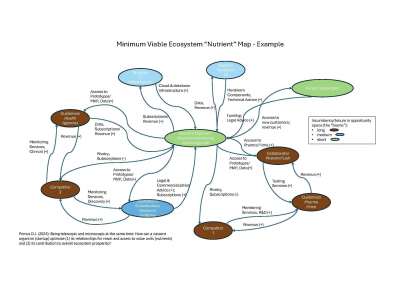

Primus' (2024) abstract suggests further use cases for the ecology lens. For example, it points out that the configuration of specific relationships within an innovation ecosystem can be optimized by a thorough understanding of "nutrient pathways", captured in an "ecosystem nutrient map" that visualizes how value units, such as financial resources or data, flow through the system. The image below illustrates how the idea of pathways of value units (e.g. data flow; patterns of sharing technological resources) can be employed to map a minimum viable ecosystem (MVE). The example is based on the emerging innovation ecosystem for a novel drug response monitoring technology.

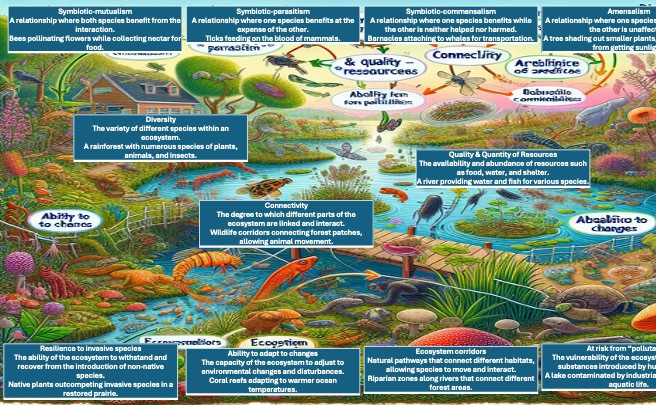

In addition to guiding the configuration of relationships, an ecology lens can also generate valuable insights via system-level indicators of function, condition and resilience - in other words, via ecosystem health indicators. Such indicators include diversity, connectivity, as well as the availability and abundance of resources in the system. Another system-level health indicator is the balance of types of relationships in the ecosystem. For instance, an excessive occurrence of symbiotic parasitism is likely harmful to ecosystem health. An example of too many symbiotic parasitic relationships in an innovation ecosystem is when startups, accelerators, consultants, and service providers cluster around a central platform or institution, extracting value without contributing proportionally. Suppose startups benefit from grants, but reinvest outside of the ecosystem, consultants charge high fees, but don't provide informal mentorship, and accelerators focus on improving their brand equity, rather than long-term ecosystem prosperity. In this case, the central institution can become overburdened; the value extraction outweighs the value creation. The following image suggests a selection of health indicators and relationship types that can be employed to address questions about the balance of relationships. Together with the indicators of function, condition and resilience, they can support the assessment of the overall health of an innovation ecosystem.

Enjoy if you decide to try the ecology lens and don't forget to provide feedback, ideas and/or insights, to djp@innovation-matters.info !

References:

Ritala, P. and Almpanopoulou, A., 2017. In defense of ‘eco’in innovation ecosystem. Technovation, 60, pp.39-42.

Dedehayir, O., Mäkinen, S.J. and Ortt, J.R., 2018. Roles during innovation ecosystem genesis: A literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, pp.18-29.

Shaw, D.R. and Allen, T., 2018. Studying innovation ecosystems using ecology theory. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, pp.88-102.

Primus, D.J., 2024. Being telescopic and microscopic at the same time: optimizing ecosystem configuration and governance with an ecology lens. ISPIM connects Osaka conference. December 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386874494_Being_telescopic_and_microscopic_at_the_same_time_optimizing_ecosystem_configuration_and_governance_with_an_ecology_lens